It contains instructions for handling, diagnosing, and altering mercury barometers. The reader does so at his or her own risk. We will accept no responsibility for damage to anyone's barometer resulting from the processes described below. If you don't feel comfortable following these instructions, then consider the well-being of the barometer and just don't handle it. Barometers are delicate and tricky to work with.

A barometer is a device for predicting weather

changes, rather than one for giving you an instant readout of current

conditions. A change in the level of the mercury indicates the passage

of a high or low pressure front over your area, and a corresponding

change in weather. Falling atmospheric pressure

precedes stormy or unsettled conditions, and a rise indicates the approach

of settled weather. Weather indications are written on the face

of your barometer to guide you.

Falling atmospheric pressure

precedes stormy or unsettled conditions, and a rise indicates the approach

of settled weather. Weather indications are written on the face

of your barometer to guide you.

In the absence of violent weather conditions, the atmospheric pressure

over the large land mass of the United States seldom varies more than

half an inch above or below the 30-inch mark (at sea level). Movement

of the mercury may take several hours or a day, and may be in very small

increments. Also, your barometer can indicate FAIR even in a rain storm,

because the narrow and fast-moving low pressure front that brought the

rain into your area passed so quickly.

Because a barometer's mercury level moves very slowly and by minute

amounts, barometers all have a "set" indicator. This will

be a hand or pointer, usually made of brass, and operated manually.

You put this marker in place next to the top of the mercury on a stick

barometer, or over the black indicator hand of a dial barometer, and

it marks the height that the mercury was at in its tube when you last

checked. This marker makes the direction of change easy to detect.

NOTE: Your banjo barometer may need a small physical jolt before the

main hand will settle into its final position. This is because the shaft

connecting the brass pulley in back to the main indicator hand on the

dial binds slightly in its tube. Just tap firmly on the wood case a

couple of times, and the hand will drop into its proper reading. Stick

barometers obviously do not require this.

BEING SURE THE BAROMETER IS WORKING

The height of the column of mercury inside its

glass tube is affected by many things that can cause the barometer to

give "inaccurate" readings, but before you can determine what

your barometer is trying to tell you, you will have to know if the barometer

is working at all or if the mercury system has a fault, and precisely

what sort of a reading you are comparing your barometer to.

1. Is the barometer actually working?

There are two forms of mercury barometer; stick (you read the mercury

height by looking directly at the top of the column inside the glass

tube, and compare it to a scale of inches printed or engraved beside

the column), and dial, also known as wheel or banjo (you read from a

hand pointing to numbers on a dial, corresponding to the height of the

mercury inside the glass tube in the rear of the barometer).

There is a quick test for each

type to tell you if you have a functioning mercury system. With the

barometer hanging on its hook on the wall, slide the bottom sideways

in an arc, to about a 45 degree angle. Do this gently, don't slap it

sideways or jerk it suddenly.

There is a quick test for each

type to tell you if you have a functioning mercury system. With the

barometer hanging on its hook on the wall, slide the bottom sideways

in an arc, to about a 45 degree angle. Do this gently, don't slap it

sideways or jerk it suddenly.

On a stick barometer, the mercury should rise smartly to the top of

the glass tube and hit the end with a "tick" sharp enough

to be heard and possibly felt through the wood of the case. The vacuum

space should fill totally with mercury, with no air pocket at the very

tip. On a dial barometer, the indicator hand (the longer, black one)

should swing clockwise around the dial, past the end of the indicated

scale. If either type of barometer fails this test, the mercury system

will need to be put back in working order by a competent restorer before

there is any point in going further.

The most common problems that prevent either stick or dial barometers

from working may be pockets of air, interspersed in the column of mercury

(and probably in the vacuum space at the top as well); some mercury

may have been lost from spillage; or the mercury itself has become so

dirty and contaminated that it can no longer function. Air often shows

up as gaps or bubbles somewhere in the length of the column, and just

one small one can stop the mercury from moving up and down.

In general, any of these problems means that the glass tube of mercury

needs to be emptied, cleaned and dried, and refilled with clean mercury

before there is any chance of the barometer working again. This is a

job for a specialist restorer (nitric acid is used to clean the inner

bore of the glass) and there is no point in wasting your money just

putting in more mercury.

Dial barometers may also have had the fiddly string linkage between

the float in the mercury reservoir and the indicator hand come off the

pulley, and this is a fault that you can correct yourself with some

patience and a modicum of mechanical aptitude.

By the way, has the mercury system been opened up to the atmosphere

so that it can work? Lots of barometer owners seem to have left the

cork stopper in the open end of the mercury tube, or have failed to

unscrew the closing screw at the bottom end of a stick barometer. See

the article on this site regarding moving and handling of barometers.

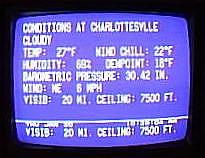

2. With what reading are you comparing your barometer?

There are many sources of readings of barometric pressure. The most

common these days is The Weather Channel on cable tv, or the evening

weather news. Be sure the tv station or other source is relatively close

to you; just a few miles can make a big difference. Also, a nearby airport

control tower, or pilots' data service, will have the current atmospheric

pressure; pilots of small planes use it to set their altimeters, which

are actually barometers. Airport readings are sometimes given as "station"

readings, which are uncorrected for elevation. Be sure to ask if you

use this source, then ask for the corrected reading, or adjust it yourself

with the table at the end of this article.

As you become accustomed to using a barometer, you'll learn to trust

the weather predictions on the register plate or the dial, and forget

the actual numbers altogether.

Atmospheric pressure

readings given out to the public by the U.S. Weather Service, and repeated

by most television weather broadcasts,are mathematically corrected for

elevation above sea level, so that weather reporting across the continent

can use standard nomenclature and also so that the weather stations

don't have to have custom-built barometers for their readings. The standard

elevation used is sea level, even if it is reported in Denver, Colorado,

a mile above the sea. This is done by taking an actual reading, then

adding a factor to it to correct for the known elevation. You will be

doing the same thing, after you read the next section.

Atmospheric pressure

readings given out to the public by the U.S. Weather Service, and repeated

by most television weather broadcasts,are mathematically corrected for

elevation above sea level, so that weather reporting across the continent

can use standard nomenclature and also so that the weather stations

don't have to have custom-built barometers for their readings. The standard

elevation used is sea level, even if it is reported in Denver, Colorado,

a mile above the sea. This is done by taking an actual reading, then

adding a factor to it to correct for the known elevation. You will be

doing the same thing, after you read the next section.

MAKING YOUR READING MATCH THE WEATHER SERVICE

If you are lucky enough to live

on the ocean front, or on a boat in the ocean, you know your elevation

is zero, or sea level (lakes don't count; the Great Lakes for instance,

are about 650 feet above sea level). The rest of us will need to find

our elevation above sea level. One of the best sources is the local

city or county engineer's office. The resident engineer needs to know

elevations all over his area for such things as water services. Just

call and ask. The office may be able to give it to you right down

to the block where you live. With that information in hand, you can

apply it as follows:

Stick barometers: There is no physical alteration you can make

to the barometer to correct its reading. Not to any of them, even

the ones with adjustable cistern capacities. They are all made to

operate at sea level, period. At elevations up to 1,000 feet, just

use the table below to make corrections to the reading on your stick

barometer and enjoy it for the lovely antique it is. At elevations

above about 1,000 feet, the common household variety just flat won't

work. Short of cutting a section out of the case and shortening the

glass tube as well, you can't make them read in synch with the corrected

broadcasts. Many owners mistakenly use the closing screw at the bottom

of the case to push the mercury up to the "right" reading,

a futile exercise. Doing this just limits the capacity of the barometer's

mercury system to accommodate high changes in volume.

At elevations

above about 1,000 feet, the common household variety just flat won't

work. Short of cutting a section out of the case and shortening the

glass tube as well, you can't make them read in synch with the corrected

broadcasts. Many owners mistakenly use the closing screw at the bottom

of the case to push the mercury up to the "right" reading,

a futile exercise. Doing this just limits the capacity of the barometer's

mercury system to accommodate high changes in volume.

You should be aware that many stick barometers are constructed with

built-in errors in the relationship between the surface of the mercury

in the cistern and the placement of the scale on the case. Fitzroys

are notorious for this; I've worked on dozens and I've yet to find

an accurate one. You can check yours with a tape measure. Measure

from any inches number on the register plate to the center of the

cistern. Twenty-nine inches on the scale should be placed 29 inches

from the center of the cistern.

Dial barometers: With the more-or-less standard 35 inch long

mercury tube that is generally used in most of these, there is latitude

for some change to adjust your reading up to elevations of a maximum

of 1,000 feet. With the barometer hanging on the wall, remove the

bezel that holds the glass over the dial. Two or three screws around

the perimeter are usually standard. Take the barometer off the wall,

keeping it upright, and open the back door. Grasp the pulley in the back between thumb

and forefinger with one hand, and with the other turn the indicator

hand on its shaft to the right reading. Put the barometer back in

its normal position on the wall and check it. A few adjustments may

be required to get the right setting of the hand on the shaft. If

you don't feel comfortable doing this, don't try it. There is considerable

potential for messing up the workings of the instrument. Read our

disclaimer.

Grasp the pulley in the back between thumb

and forefinger with one hand, and with the other turn the indicator

hand on its shaft to the right reading. Put the barometer back in

its normal position on the wall and check it. A few adjustments may

be required to get the right setting of the hand on the shaft. If

you don't feel comfortable doing this, don't try it. There is considerable

potential for messing up the workings of the instrument. Read our

disclaimer.

If you reside above 1,000 feet and want your dial barometer to

be accurate, a shorter mercury tube can be fabricated and installed.

We've done several and they have all worked, up to 6,800 feet in one

case. It isn't particularly expensive, and nothing is damaged by installing

a shorter tube in the case. The chances of the tube you have now of

being original, or even over 100 years old, are slim to none. Old

glass corroded away in contact with mercury, and the tubes were replaced

wholesale in order to keep the barometers working. Yours has probably

been done several times, so replacement has no effect on the antique

value of the instrument as a whole.

In conclusion, a scientifically precise reading from your barometer

doesn't really matter, in the grander scheme of things. As long as

the mercury level drops when a storm is coming and rises for fair

weather, that is really enough of an indicator to make it a good predicting

device. That's all it did one or two hundred years ago, and it was

good enough then.

ALTITUDE CORRECTION TABLE

FOR STICK BAROMETERS

|

(feet) |

(inches) |

(feet) |

(inches) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Use this table to correct your reading. For instance,

if you live at 600 feet elevation and your barometer reads about 29.31,

and the weather news says the current barometric pressure is 29.95 inches

of mercury, just find your elevation in the table above and add .64 to

29.31. |